It Doesn’t Seem Real Until it Happens to You

Yes, folks, it finally happened to us. We had a good run, but the dieback got us, right in the Bridgwater Road, which will be closed for five days this October to take down infected Ash trees.

Ash saplings infected by the Chalara fraxinea fungus were found at Buckingham Nurseries at the beginning of 2012.

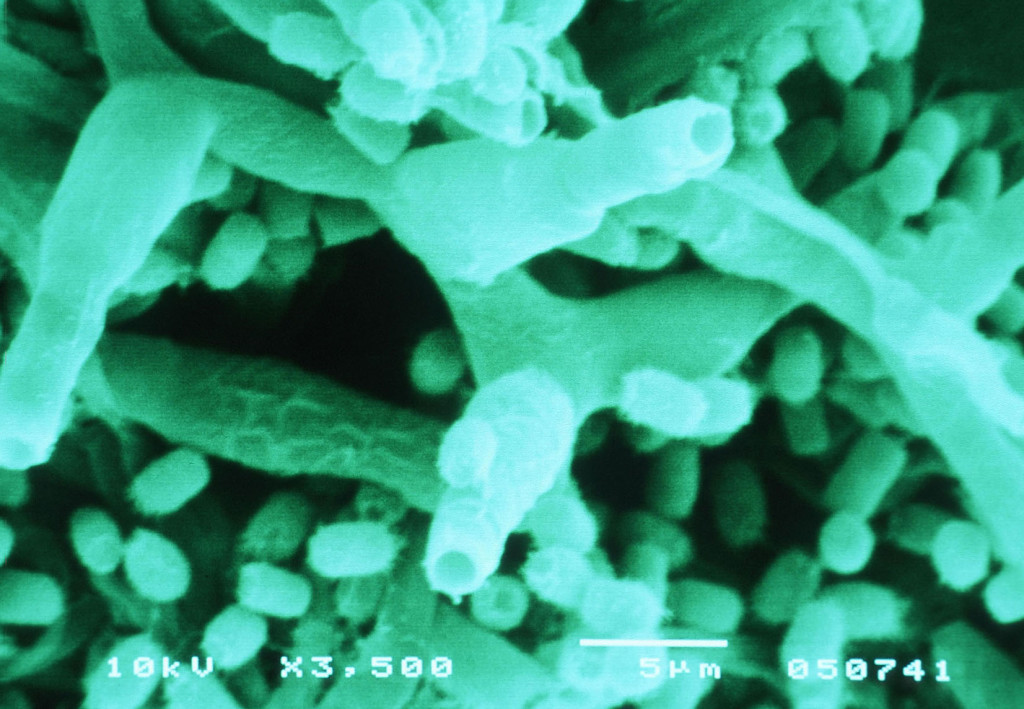

Here is the first known selfie of the Ash dieback fungus formerly known as Chalara fraxinea or Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus: Hymenoscyphus fraxineus.

Back in 2012, the concern was that this plague, which creeps inexorably through air, soil, and aboard insects, would pierce our beloved Common Ash in leaf and stem, leaving no survivors.

Of all the trees, that grew so fair…

But in 2024, there’s good news: Chalara / Hymenoscyphus (which only affects Common Ash, Fraxinus excelsior, not any other tree, including Mountain Ash, which is the unrelated Sorbus aucuparia) is not a methodical assassin.

Ash trees have varying degrees of resistance: many do die, but many are only scorched, losing limbs while the rest of the tree carries on.

Some mature trees only experience partial die back, and then recover in other places, although none seem to be immune.

Trees in woodland seem more susceptible, while trees out by themselves in the open, or in urban areas with no bare soil around and fungicidal, dry, polluted air seem to be much less affected.

So, while Ash is going to decline (and cost a lot of money tidying up in the process), it isn’t going extinct just yet, and should be much less affected than Elms were by Dutch Elm Disease.

Management of Ash Die Back is in full swing, you’ll find everything you need here on the Gov website, with specific advice for people who just own one or a few ash trees, and for people managing Ash woodland.

From the University of Vienna, we have a 240p potato-quality video of the release of fungal spores from ash twigs infected with the reproductive stage, which was originally named Chalara fraxinea, since updated to Hymenoscyphus fraxineus.

It was filmed in 2012, so that’s why it looks like it was filmed in 2006.

Back in 2012, we were fortunate to talk with tree experts at the Institute of Forest Entomology, Forest Pathology and Forest Protection, IFFF. They shared the images below with us, and we spoke about doing what we can to sensibly limit the spread of the disease. A mad rush to deforest Ash could remove genetically resistant trees, and interbreeding those trees is the key to resistant Ash populations in the future.

If all goes well, it could be possibly to re-introduce highly resistant Ash trees in the future.

Ash tree dieback disease images

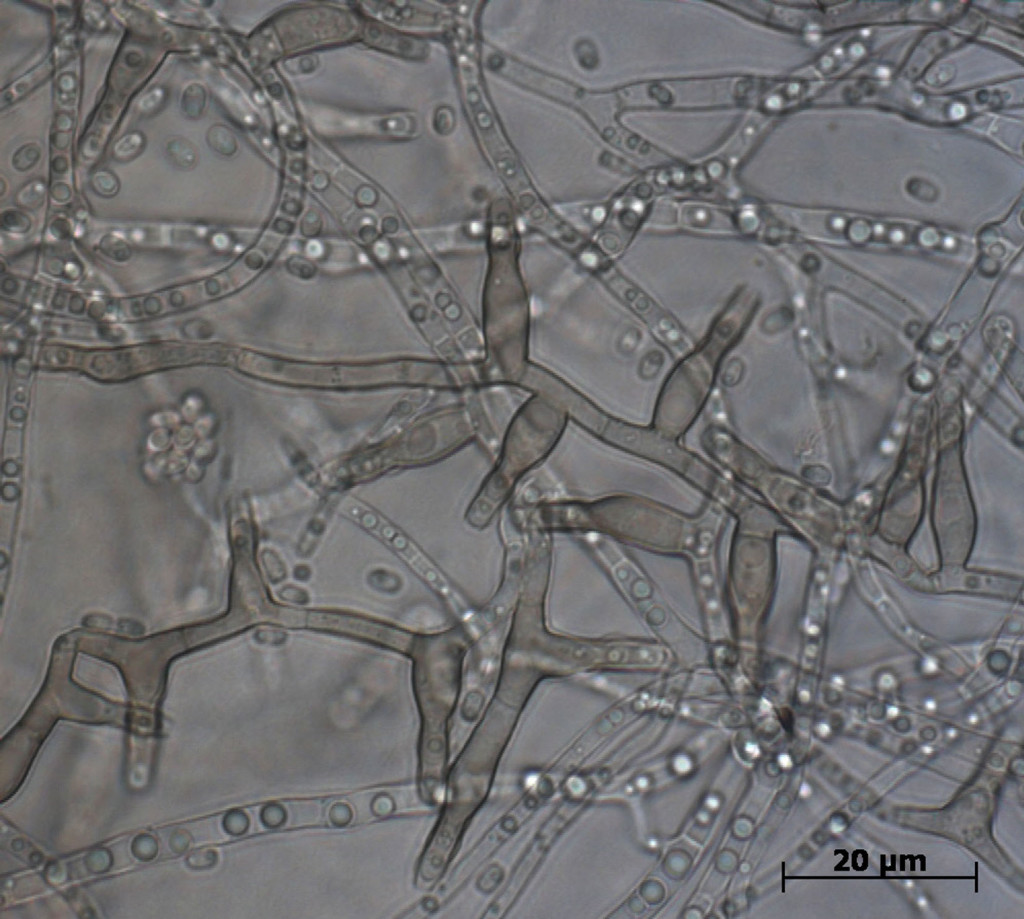

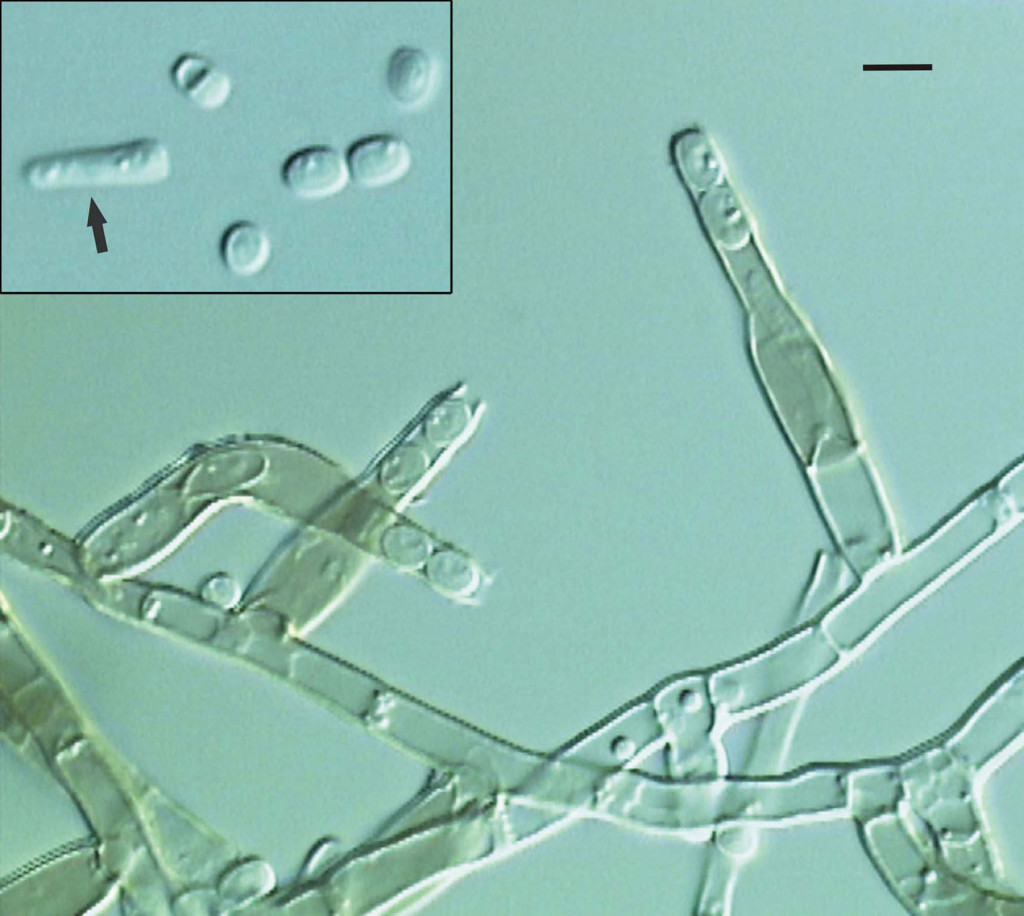

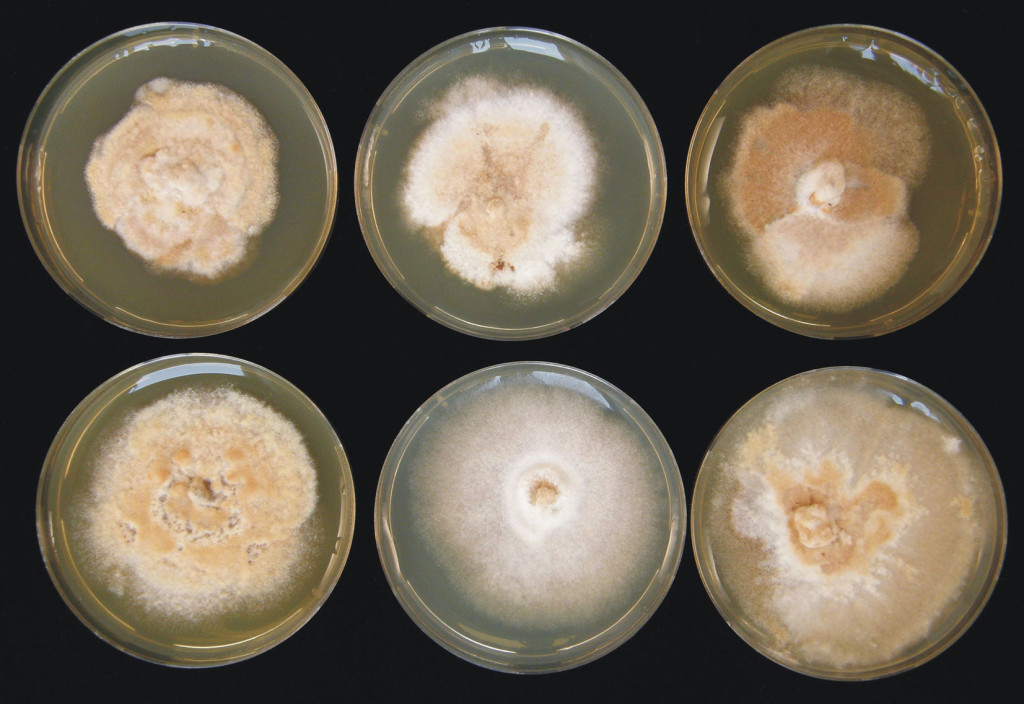

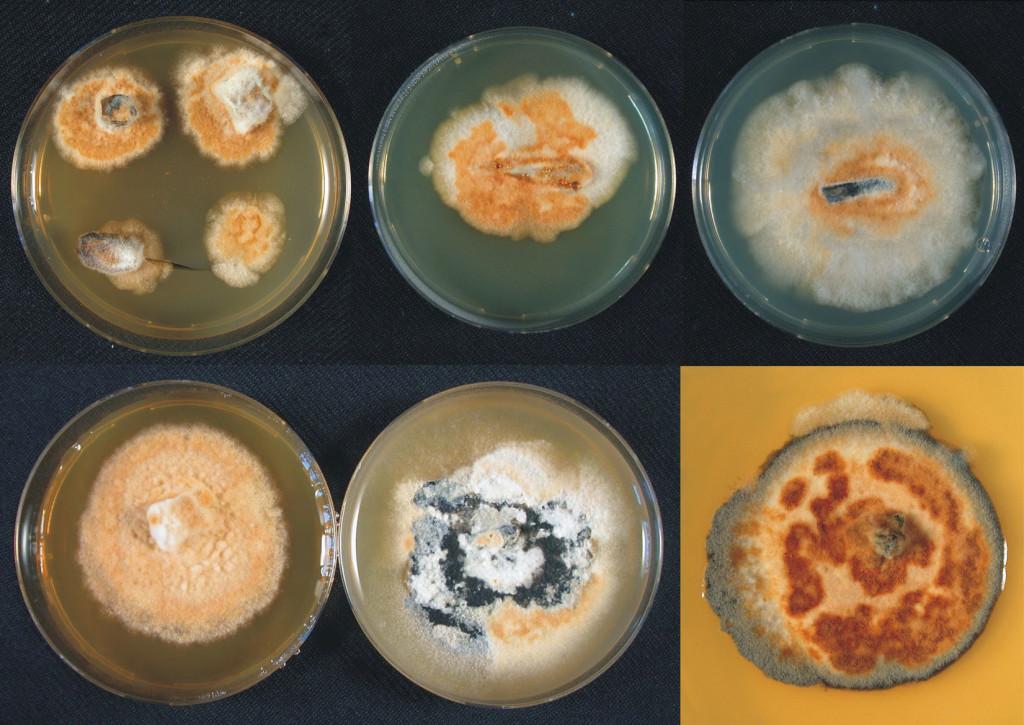

Images include microscopic images of the pathogen, lab-grown fungal cultures, branch and stem lesions, leaf wilt, and crown dieback.

Diseased leaves, twigs and branches eventually fall to the floor, setting the scene for the reproductive stage of the fungus – a trumpet-shaped mushroom

(credit: Thomas Kirisits)

(credit: Thomas Kirisits)

Cultures of the fungus, grown for research purposes at the IFFF in Vienna.

How to Identify Ash Die Back Disease

A tell-tale sign of ash dieback disease is a necrotic lesion (tissue death) on stems, twigs and branches:

Once the fungal infection spreads fully across a stem or branch, nutrition is cut off beyond that point and leaves begin to wilt and die.

Continued leaf loss works its way back towards the trunk of the ash tree:

(credits: Josef Wampl, Thomas Kirisits)

(credit: Thomas Kirisits)

(credit: Thomas Kirisits)

Cross-sections of dead wood show how far into the trunk necrotic lesions can reach

Has ash dieback disease come to your area?

Image credits: By kind permission of Thomas Kirisits, Josef Wampl, Christian Freinschlag, Katharina Kräutler and Michaela Matlakova of the Institute of Forest Entomology, Forest Pathology and Forest Protection (IFFF), Department of Forest and Soil Sciences, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna (BOKU), Vienna, Austria

Should we avoid putting leaves in compost bins?

Are spores likely to spread to other plants should the compost then be used on the garden?

Hi Sheryll,

If you have ash trees in your garden, and you’re not sure whether they’re healthy, the safest route will always be to dispose of all leaf and twig litter by burning.

The fungus itself can be carried around by touch (on boots, wheelbarrows, tools, pets, etc), so in theory it can be ‘on’ the leaves and twigs of other trees (what scientists call a ‘vector’ for the infection). But it won’t infect those other trees – it’s important to remember that this fungus will only infect ash trees.

If you don’t have ash trees in or near your garden, you shouldn’t worry – compost away!

A lot of really good info here thanks guys, a credit to the gardening community!

This has been helpful. We live near a wooded area in Lanc’s and have 2 large ash in the garden. The smallest one is obviously infected. Both trees are about 50 plus years old. I am happy to leave them alone apart from some pruning. They are an important part of the hedge row which is mostly hawthorn and is the boundary to the property.

More advice would be helpful.

I think that the government website on this matter is the most definitive place to look (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ash-tree-research-strategy-2019), or the Woodland Trust (https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/visiting-woods/tree-diseases-and-pests/key-threats/ash-dieback/your-questions-answered/) or the RHS website (https://www.rhs.org.uk/advice/profile?PID=779).

My mountain ash (rowan) died of a honey fungus infection this year. Ash are resistant to honey fungus, rowan are resistant to ash dieback. It doesn’t really matter to the tree which fungus kills it.

A dead tree is a dead tree, I agree, but the fungi are quite different.

Honey fungus attacks through a “root system” that travels relatively slowly but kills fast. It is not species specific, and very few tree species are truly resistant.

It is potentially preventable: planting susceptible trees inside an impermeable barrier in the top 6″ of soil should keep them safe. It also tends to attack weaker and more stressed subjects, so the best prevention is healthy soil with loads of mulch to produce healthy plants.

Ash die back, however, is spread by the wind and so travels fast. It is specific to the Fraxinus family only, and attacks them all, regardless of the tree’s health. It is neither preventable nor treatable, but unlike Honey Fungus – which is a guaranteed death sentence, eventually – it seems that some Ash trees have a degree of resistance.