Habitat Aid is our all-time favourite, award-winning, impact driven, Somerset based business founded in 2008, and their hedge planting video is educationally inspirational

Native hedge plants are proven to be tough as cookies made of brass monkeys, and Habitat Aid demonstrate how rough and ready you can be with them.

Hawthorn in particular is absurdly resilient. If we weren’t so charming, we could sell leftover bareroot Hawthorn from April the following November, and no one would notice, it’s so strong.

We are busy updating our world-famous native country hedge planting video, so we’re checking out the others’ efforts, ‘mirin’ a little bit, you know:

We love it! Get them planties planted, bish bash bosh.

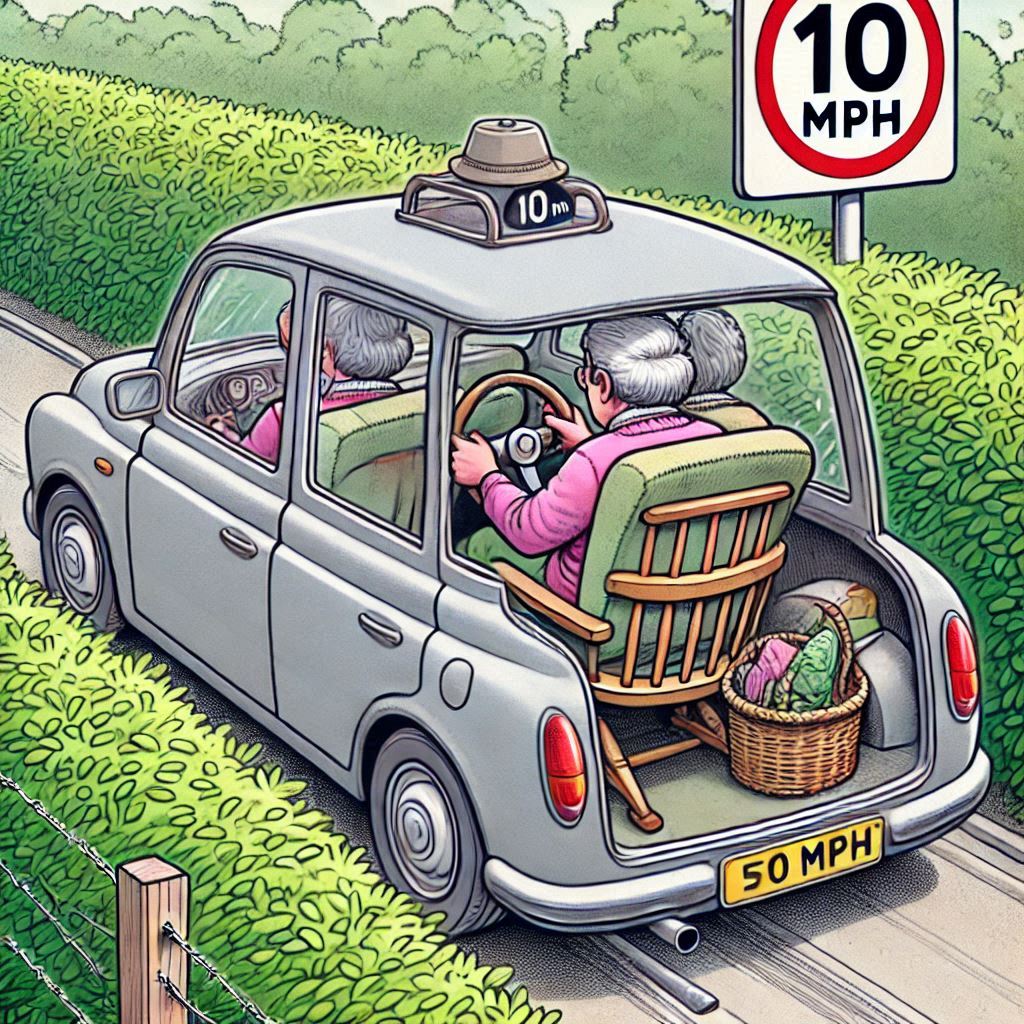

And still, what would life be without a little backseat drive?

Keep those roots moist

No one likes a dry root, that should have gone without saying, and these dusty looking specimens are not what we like to see: tut-tut!

At Ashridge, we constantly harp on about the importance of keeping the roots moist at all times before planting.

We guarantee those plants, so we feel entitled to lecture you about looking after them.

“Don’t be so insufferable”, says Habitat Aid: your plants won’t die if the roots look dry on the outside for five minutes, and that’s true.

The thickest, juiciest, triplest hedge yet

A triple row hedge! Up to 10 plants a metre! Nick, I could kiss you if I weren’t saving myself for Monty.

I’ve been promoting double row country hedges at 6 plants per metre as per the Countryside Stewardship BN11 grant requirements all this time, as though I were a mere cog in a machine.

It’s as if my eyes could see, yet lacked vision.

To everyone who feels like planting an extra row in your hedge: we support your decision fully.

You don’t need to plant in groups

It doesn’t matter, do what makes you happy, the important thing is to mix the plants up well so you don’t have blocks of one species in a supposedly mixed species hedge.

Nick suggests planting in blocks of 3-5 plants of one species, to which we would say OK, but three is better than five, and definitely not more than five.

In most hedge packs, one species will make up the majority of the mix, usually Hawthorn. It’s important to spread that “backbone species” quite evenly along the hedge, so that every metre has at least one.

Nick mentions some plants not to plant groups, like wild roses, wild honeysuckle (not shrub honeysuckle, which isn’t native), or Holly, which is a super choice for the shadier middle row of the triple row, King Girth Hedge above.

You can add native honeysuckle to a native hedge

You know what? Ashridge does not sell wild Lonicera periclymenum, the native honeysuckle or woodbine, and Habitat Aid does. We only sell cultivated varieties of L. periclymenum like Scentsation.

In our opinion, wild roses are the best lanky plants for scrambling through a hedge: very thorny and well-behaved.

Wild honeysuckle is thornless, vigorous, and grippy, so it tends to need managing in a new hedge to prevent it from smothering its neighbours.

Plant at least a metre from a fence etc

Nick’s right: if you plant your hedge right up against a fence, it will grow through and/or push against it, causing problems later.

If you plant right up against a wall, you limit the growth and risk planting into a dry spot.

Using an organic mulch like bark is better for soil than plastic mulch (or nothing!)

If it’s feasible, we 100% agree with Nick that organic mulch like bark is literally a billion times better for the soil than woven polypropylene weed suppression fabric; the brands everyone knows are Mypex and Terram.

A good layer of organic mulch will also preserve much more soil moisture.

Yes, organic mulch needs more maintenance: weeds still grow on it, and it rots away within a year or two.

That’s fine in the garden or other convenient to manage site, but a farmer with miles of hedge doesn’t need that chore on their list.

Chances are, British weather will water your native hedge plants for you

According to Ashridge’s official watering policy, we really shouldn’t agree with Nick’s assertion that your plants won’t need much water, and one should wait until they are in distress before giving them a thorough watering.

But it’s based on experience. Native British hedge plants are troopers. You can feed them hardship for breakfast, and they’ll hand you flowers at lunchtime.

A typical British year has rainy spells in every month, so unless there is a drought, the chances are good that you can get away with between one and zero waterings, especially on heavy, clay rich, water retentive soils, double especially with that lush carpet of bark mulch Nick recommends.

Then Nick goes on to say that giving plants a little water is worse than nothing, because it encourages shallow root growth.

Fair enough about deep watering being better than light watering, but are shallow roots really worse than dead roots?

Still, we do disagree a bit. Watering your plants in their first year is very good for them. Water is an input for photosynthesis. If it’s limited, the plant’s growth will be too.

A wise move is to keep an eye on the weather forecast. When a dry spell of 3+ weeks is predicted, give your plants a good soak as soon as you see the top layer of soil get dry.

Slit Planting is Easy

There are armies of professional planters who slit in Sitka spruce like the hounds of Hell are behind them, and they get an 80-90% success rate.

Sure, best practice is to avoid “J root”, where you stuff the roots down a slit that’s too small, and the ends of the roots bend round and end up near the top of the hole.

That’s potentially happening here, where it would have been easier to remove the mulch first.

A spade with a longer head for wiggling a wider slit makes this job easier; a long nose trenching spade is great, and you can do two slits side by side for cumbersome roots.

But again, a scrap of straggly J root is no problem about when you’re talking about robust young native plants, several of which will grow from seed in a crack in an old brick wall.

Life’s too short, just sprinkle Rootgrow on the ground!

This devil may care style is another savvy move from Nick; buy Rootgrow, chuck it on the ground, live life on your terms:

In our quick guide to applying Rootgrow, we suggest trying to get it down the planting hole and onto the roots, but no one likes a pedant.

The fungi aren’t going to get lost, they’re going to get washed straight down onto the roots, job done.

Cut those plants in half before it’s too late…

It looks like Nick is not hard pruning his hedge by the traditional 50% after planting (you only do this to native hedge species, not any garden hedge). We expect that’s deliberate, but the rogue mastermind doesn’t elaborate.

Cutting back native hedging after planting, and again in the second year, is the traditional way to create a bushy hedge from the base up.

That said, the BN11 countryside stewardship hedge grant only asks that you “trim the newly planted hedge in at least the first 2 years to encourage bushy growth, allowing the hedge to become taller and wider at each cut”.

Exactly how you trim it is up to you.

Who did this? That’s not funny! I’m so sorry, Nick, it won’t happen again.