“Latin” plant names aren’t really Latin, as in the language of the Roman Empire, they are a mix of words and names from Latin, Greek, and other languages

“Latin names” is easier to say than Binomial Nomenclature, which means “two part naming system”; that’s lovely, but still doesn’t explain much.

Why are these alien sounding names, littered with italics and quote marks and abbreviations, necessary?

Why can’t people use the regular old common names for plants?

A daisy’s a daisy’s a daisy, why do we have to complicate everything? Why bother with Bellis, and Erigeron, and Argyranthemum, and how are they all Asteraceae?

There are loads of different kinds of daisies, and they can have different common names from one county to the next, never mind countries.

For example, the wildflower Field Scabious, is also known as Lady’s Pincushion, Gipsy Rose, and Blue Bonnets – in England. In France, some call it Ass’ Ear. That’s just one reason why the English Channel is necessary.

But wherever you are in the world, the scientific, botanical, “Latin” name for that plant is Knautia arvensis. This guarantees that people know what you’re talking about, whether at a garden centre, on Gardeners’ Question Time, or when you are lost in the French countryside and desperately need to feed your pet narrow-bordered bee hawk-moth, Hemaris tityus.

It’s a bit like in a nation: the Asteraceae (daisy) nation is made up of clans called genera (singular: genus), such as Bellis, Erigeron, and Argyranthemum.

Each clan is made up of family units called species with their own names, where the clan / genus name comes first, and the family / species name comes second, like Bellis perennis (Common daisy) or Erigeron karvinskianus (Mexican Fleabane Daisy).

Within those family units, there are often further subdivisions, called subspecies and cultivars, which I’ll explain more below.

But first, a bit of history.

Who came up with all this binomial naming business?

An aptronym is “a name that is regarded as amusingly appropriate to a person’s occupation”.

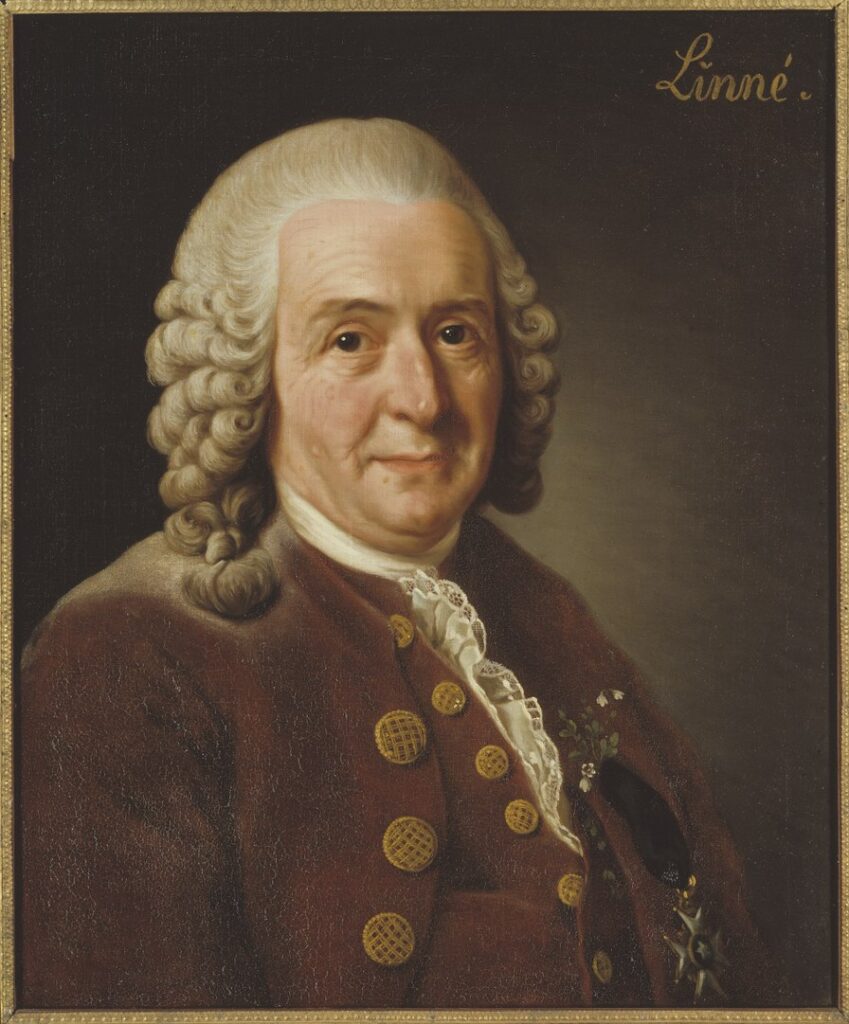

The man popularly believed to be the father of the binomial naming was Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), whose surname means lime or linden, as in Tilia platyphyllos, the popular roadside tree that covers your car in sticky aphid poo all summer.

Limes and Willows made the best charcoal for gunpowder, so the name would have sounded cool back when Carl’s father chose it.

Charlie Limes’ Wikipedia page makes for a fun read; the part about him attending “Harderwijk, a university known for awarding degrees in as little as a week” might raise some eyebrows.

But any suspicion will surely be settled by the next paragraph, where we learn that he worked twice as hard as the other students: “within two weeks he had completed his oral and practical examinations and was awarded a doctoral degree.”

Carl’s level of academic brilliance is confirmed by the fact that “binomial nomenclature, was partially developed by the Bauhin brothers … almost 200 years earlier … Linnaeus was the first to use it consistently throughout the work, including in monospecific genera, and may be said to have popularised it within the scientific community.”

Good enough for me!

What do these Latin / Greek / Whatever botanical names mean?

The best place in the world for learning the meaning of botanical names is Dave’s Botanary, a resource so fine that Carl himself might have stolen popularised it.

Many of these names are perfectly logical, when you know what they mean.

The wild sweet cherry tree, known in some parts as a Gean tree, is Prunus avium.

Prunus is from the Latin for a plum or cherry tree. It is one genus, or major branch, of the Rosaceae (rose) family.

Within each genus, there are one or more species, or forms, each with their own name, in this case avium, meaning “of the birds”, which love to guzzle the fruit: small birds will peck the tops off, generously leaving you the bottom half.

Other species in the genus Prunus include the inedible Bird Cherry, Prunus padus, and the evergreen hedge plant Cherry Laurel, Prunus laurocerasus.

Naturally occurring variants of species are called subspecies: the line between a subspecies and different species is not set in stone, but the rule of thumb is how well they interbreed.

Horses and donkeys are different species because while they can breed, their offspring are infertile, whereas Bengal, Sumatran, and Siberian tigers are subspecies of tiger that look quite different, but can breed successfully.

OK, so that explains species: what are cultivars?

Mathematicians have shown that biologists are yet to produce a plausible hypothesis for the origin of species in nature, but that is not the case with cultivars, a portmanteau of “cultivated variety”.

Cultivars are roughly equivalent to breeds of dog: subspecies that were discovered or deliberately bred, then named and propagated by humans, often with significantly different characteristics to their parent species.

The convention is to put the plant cultivar name in single apostrophes after the species name.

For example, wild Prunus avium fruit are not really nice to eat unless cooked with sugar, but cherry cultivars like Prunus avium ‘Stella’, Prunus avium ‘Lapins Cherokee’, or Prunus avium ‘Sunburst’ are absolutely delicious off the branch.

Unlike dog breeds, most plant cultivars can only be propagated by cloning through grafting or cuttings: you can’t grow a Sunburst cherry tree from a Sunburst cherry seed.

How Do I Pronounce Botanical Names?

Some names are easy to pronounce, like the Ghost Bramble, Rubus cockburnianus: Rub-us cock-burn-eeeeeee-anus (one more time and you are so fired – ed).

These lines on cyclamen, from an old gardening periodical, show that this question of pronunciation has been pondered long and hard for many years:

“How shall we sound its mystic name

Of Greek descent and Persian fame?

Shall “y” be long and “a” be short,

Or will the “y” and “a” retort?

Shall “y” be lightly rippled o’er,

Or should we emphasize it more?

Alas! The doctors disagree,

For “y’s” a doubtful quantity.

Some people use it now and then,

As if ’twere written “Sickly-men”;

But as it comes from kuklos, Greek,

Why not “kick-laymen,” so to speak?

The gardener, with his ready wit,

Upon another mode has hit;

He’s terse and brief — long names dislikes,

And so he renders it as “Sykes.” “

The pronunciation of your plants’ “Latin” names really doesn’t matter: they’re your plants, you can do as you please with them: tomato, tomahto.

Enlightening! Thankyou very much, never knew the rationale before now.

You are welcome (a mere 6 years later)!